Charles Page

On 3rd September 1940, the Margate lifeboat was searching the North Sea for a downed pilot, who had come down seven miles off north Kent. After some ninety minutes searching, the lifeboat was about to turn back, when the crew spotted the pilot entangled in his parachute.

RAF fighter pilot, Richard Hillary was suffering from severe burns, and had already resigned himself to death. He attempted to hasten this, by deflating his Mae West, but his parachute kept him afloat, and he was unable to release the buckle. There was nothing more he could do but shout to the sky, and as he later recalled, ‘There can be few more futile pastimes than yelling for help in the North Sea with a solitary seagull for company.’ Unknown to Hillary, his parachute descent had been observed by a coastguard, and the lifeboat J.B. Proudfoot was already searching.

Hillary’s mind was already adrift, when eager crewmen hauled him into the lifeboat. He was a grim sight, with hands burnt and deformed, and his face hanging in shreds. One of the crew found his mouth and poured some rum into it, though this was hardly enough to dull the shock and pain. By a strange quirk of fate, one of Hillary’s ancestors had been a founder of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

Richard Hope Hillary, who wrote the WWII classic The Last Enemy, was born in Sydney on 20th April 1919. His grandfather, Thomas Hillary, had run a sheep station in South Australia. His father, Michael James Hillary, was born in Carrieton, South Australia in 1886, while his mother, Edwyna (nee Hope) was from north-west Australia. During WWI Michael Hillary was a Captain in the AIF, served with the Australian Wireless Squadron, was twice Mentioned in Despatches, and won the DSO and OBE for service in Mesopotamia. He later became Private Secretary to Prime Minister Billy Hughes. Certainly, Richard Hillary had a rich Australian heritage.

In 1923, Michael Hillary transferred to Australia House in London. Three years later he left for a government position in the Sudan, and Richard was placed in boarding school in England. On one school holiday he visited his parents in Khartoum. They spent much time in the hotel swimming pool, which had a high diving board. The young Richard was determined to dive, but from the height, he almost baulked, before his courage took over. This became the pattern of his life – that he would never give up.

At the age of 13, he was sent to Shrewsbury Public School, where he informed his English teacher that he wanted to be a writer. He also developed a passion for flying, after his father took him to Sir Alan Cobham’s Flying Circus in 1933. Richard enjoyed a short joy flight, and then volunteered for aerobatics with the great man.

Then in 1937, he was accepted at Trinity College, Oxford, where he learned to fly with the University Air Squadron and gained a rowing ‘Blue’. Hillary and his crew made an unofficial trip to Germany, where they surprised the well-drilled German crews and won the Hermann Goering Rowing Cup.

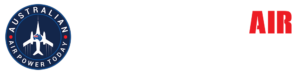

Richard Hillary was an individualist with a slightly arrogant manner, softened by an easy charm and a keen sense of humour. His tall, athletic good looks, made him very attractive to women, and he in turn, was very attracted by them. Life at University was a pleasant mixture of rowing, flying, holidays in France or Germany, parties, girls, and occasional study. Yet, Hillary and his peers were something of a lost generation, seeking a cause. However, they knew war was coming.

In October 1939, Hillary joined the RAF, and trained as a fighter pilot. After a stint flying Lysanders at No 1 School of Army Co-operation, he was posted to 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron, based at Montrose, Scotland. To his great delight, Hillary was allocated his own Spitfire Mk 1a, s/n L1021, which he named ‘Sredni Vashtar’ after the fierce ferret in a short story by Saki (pseudonym of H.H. Munro). The squadron flew patrols in the area, and also performed flypasts and aerobatics for the children of nearby Tarfside, who idolised the fighter pilots.

After the squadron moved south to Hornchurch, Hillary found himself in the thick of the Battle of Britain, dog fighting over the Kent countryside. He was credited with five Me109s shot down, plus two probables, and one damaged. Hillary himself was shot down over Kent on 29th August 1940. After crash-landing his Spitfire in a cabbage patch, he made for nearby Lympne castle, where he ‘gate-crashed’ a Brigadier’s cocktail party.

However, his luck ran out on 3rd September 1940, when after shooting down his fifth Me109 he was in turn shot down by Hauptmann Erich Bode of II/JG26. Hillary had trouble with his canopy jamming before take off, and now it jammed while he was trying to bale out. He was badly burned before it finally opened, but he then passed out. Luckily the Spitfire flipped over and he fell out, and recovered in time to open his parachute. After his rescue by the lifeboat he was taken to Margate Hospital, and then the Royal Masonic Hospital in London.

Hillary had suffered horrific disfiguring burns to his face and hands, and endured a long period of plastic surgery as a ‘guinea pig’ in Sir Archibald McIndoe’s ‘beauty shop’ at East Grinstead (the town that never stared). This painful and frustrating time gave Hillary much pause for reflection and with a pencil in his distorted left hand, he began to write.

After his discharge from hospital, Hillary had another narrow escape, while downing a pint at the ‘George and Dragon’ in Knightsbridge. Hillary ignored the eerie wail of the air raid sirens, but just as he finished his beer, a stick of bombs advanced towards the pub, each crump louder than the last. All conversation stopped, as the whistling of a falling bomb rose to a crescendo and sent everyone diving to the floor. The shattering blast left the pub a shambles, but the house next door took the full force of the bomb. Hillary scrabbled frantically through the rubble and helped to pull out a dead baby. He then found the badly injured mother nearby and gave her a sip of brandy. The mother took one look at Hillary’s face and said, ‘I see they got you too.’ Then she died.

As Hillary was still unfit for active duty, he was sent by the Ministry of Information on a public relations visit to America. He sailed to New York on the MV Britannic, which lost its escort to the hunt for the Bismarck. On arrival, he was attached to the Air Mission in Washington DC, and also spent time in New York. Although kept out of sight, he gave several radio talks and an interview on NBC, wrote articles, and was feted as a war hero. He was befriended by many celebrities, including the actress Merle Oberon, with whom he had a love affair. Hillary also met the great French author-pilot, Antoine de Saint-Exupery, who introduced him to his publisher.

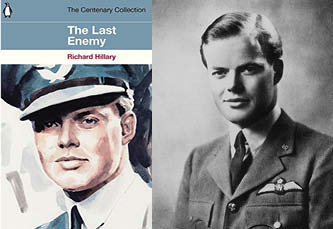

By now, Hillary had completed his manuscript, which went on to become one of the most acclaimed books to come out of the war. It was first published in America in1942 under the title, Falling Through Space. The book was praised by the New York Times, the New Yorker, author J.B. Priestley and many others. After Hillary returned to England, it was published by Macmillan, who re-titled it The Last Enemy. The title of Richard Hillary’s book was taken from Corinthians 15:26 – ‘The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death.’ The book relates the author’s growth out of an idyllic youth into a maturity accelerated by the war. Hillary’s graceful style turned a ‘war’ book into a well-loved classic. His publisher and biographer, Lovat Dickson, declared, ‘Here is a writer who happened to be a pilot, not a pilot who happened to write a book’.

Hillary then attended a Staff College course, and scripted an Air Sea Rescue documentary. He gained a wide circle of literary and artistic friends, including Mary Booker, who was related to the poet W.B. Yeats. Mary Booker was to become the love of Richard’s life. He also met RAF artist Eric Kennington, who persuaded him to sit for a portrait. This portrait was later placed in the National Portrait Gallery.

Richard Hillary was a legend now, both as a war hero and as a successful writer. However, many of his close friends had been killed in action, and he felt compelled to honour them and ‘go back’ to active duty. He was still having problems with his hands and eyes. On his left hand he could move his thumb and index finger, and on his right hand he could only move his thumb. He could not even use a knife and fork, but persuaded the authorities to post him back to operational flying. His C in C, Air Vice Marshall Sholto Douglas later regretted this fateful decision. Hillary reported to No 54 OTU night-fighter training unit at RAF Charterhall, in Scotland. The base was known by the locals as ‘Slaughter All’ and in the last eight months of 1942 there had been 97 crashes and 17 deaths.

Hillary found himself flying an obsolescent twin-engine Blenheim at night, in thick cloud, howling winds and icing. He could only see out of one eye, and his hands were still so deformed that he had trouble operating all the knobs, buttons, levers and controls. Indeed, McIndoe had written to the station medical officer, asking that Richard be sent back for more treatment. Yet Richard was determined to stay the course, fearing failure more than death. While on leave he told his friend, legless pilot Colin Hodgkinson, ‘I don’t think I’ll see you again … I don’t think I’m to last it out’.

Prophetically, his was a tragedy in the making, and on 8th January 1943, he was killed in a night flying accident. Flying in a Blenheim Mk V, with his radio operator Sgt Wilfrid Fison, Hillary was orbiting the airfield beacon light, when the Blenheim spiralled down and crashed into a field at Crunklaw Farm. The aircraft exploded into flames. Several farm workers attempted to recover the crew, but there was nothing to be done. Richard’s gold watch was later found some distance away.

Although it was thought that Richard had lost control due to his weak hands, another pilot, Andy Miller, stated that he had suffered icing the same night and had aborted his exercise and returned to the airfield with some difficulty. It may well have been a combination of these two factors.

Richard Hillary was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium, where he is commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. His ashes were scattered from a RAF Boston by Hillary’s former 603 Squadron C/O, George ‘Uncle’ Denholm, over the same area where Hillary had been rescued. At the same time, a memorial service was held in London at St Martin-in-the-Fields. Some 1500 mourners attended, including Dennis ‘Sinbad’ Price and Henry ‘Mussel’ Sandwell from the J.B. Proudfoot lifeboat.

In later years an annual lecture was held in his honour at Trinity College, as well as an annual literature prize. Then in 2001 a memorial to Richard Hope Hillary and Kenneth Wilfrid Young Fison was unveiled close to the accident site near RAF Charterhall. It is hoped that Richard Hillary will also be recognised and honoured in the country of his birth. Meanwhile, his eloquent voice may be heard on several media sources.

Sources: NAA, AWM – Michael Hillary

Imperial War Museum

Channel 4 TV doc

Audio From the Past, youtube

Bibliography, The Last Enemy, Richard Hillary

Richard Hillary, Lovat Dickson

Mary and Richard, Michael Burn

Richard Hillary, David Ross

Australian Air Aces, Dennis Newton